By: Dipin Sehdev

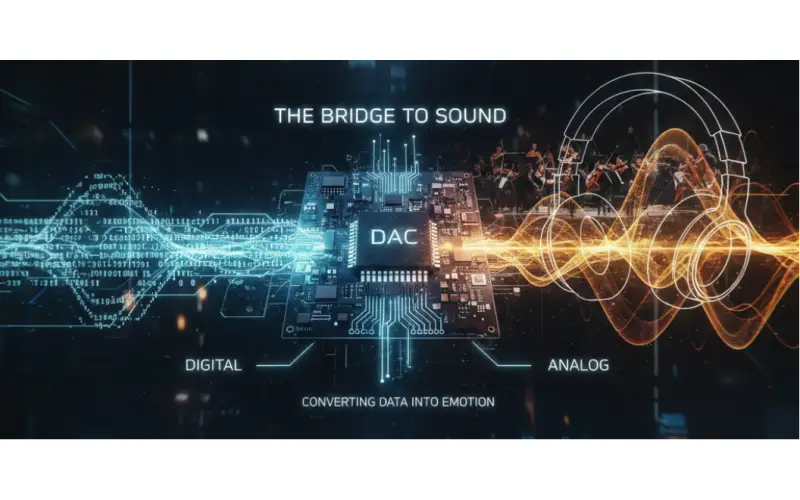

The Invisible Component Shaping Every Digital Sound You Hear

If you’re reading this on a phone, laptop, or tablet, there’s a very good chance a digital-to-analog converter—better known as a DAC—is working right now. It’s sitting quietly between the digital world and your ears, turning streams of ones and zeros into something that sounds like music, dialogue, or explosions.

And yet, despite being one of the most important components in any audio system, DACs are often misunderstood, overlooked, or reduced to a spec sheet bullet point.

That’s a mistake.

DACs don’t just exist in audiophile and A/V gear. They’re everywhere. Your phone has one. Your laptop has one. Your TV has several. Bluetooth speakers, soundbars, powered speakers, headphones, game consoles, AV receivers—all of them rely on DACs to do one thing correctly: convert digital data into analog sound without losing timing, detail, dynamics, or musicality along the way.

Once you understand that everything digital must pass through a DAC before you can hear it, a more interesting question emerges:

If all DACs do the same job, why do they sound so different?

The answer explains why companies invest so heavily in DAC design—and why choosing the right one matters more than most people realize.

What a DAC Actually Does (And Why It’s Harder Than It Sounds)

At its core, a DAC converts digital audio data—PCM or DSD—into an analog voltage that can be amplified and sent to speakers or headphones. That sounds straightforward. It isn’t.

Digital audio is fundamentally time-based. A DAC isn’t just converting numbers into voltage—it’s reconstructing a waveform at precisely the right moments, thousands or millions of times per second. Any error in timing, noise, power delivery, or signal handling affects the final sound.

This is why two DACs using the same chip can sound noticeably different.

The chip itself—whether from ESS, AKM, or Cirrus Logic—is only part of the story. Everything around it matters just as much:

-

Clocking and jitter control

-

Power supply quality (both main and local regulation)

-

Output stage design

-

Digital filtering and DSP implementation

-

PCB layout and grounding

-

Input handling (USB, HDMI, optical, coaxial)

As Anders Ertzeid from Hegel puts it, the industry has largely solved the basic problems—but the real gains now come from refinement:

“Most focus has been put on jitter reduction and clocks. We feel the best manufacturers are quite good at this now, so the biggest focus right now may be on power supplies. Both main and local. Basically jitter and noise are key elements.”

That’s why DAC design is still one of the most challenging areas of audio engineering. It’s not about chasing numbers—it’s about managing noise, timing, and stability in a world that’s becoming more complex every year.

One Chip, Many Sounds: Why DAC Implementations Differ

It’s true that most audio companies rely on a small number of DAC chip manufacturers. ESS and AKM dominate the market today, with Cirrus Logic filling key roles in mobile and consumer electronics.

But a DAC chip is not a DAC.

Think of it like an engine. Two cars can use the same engine block and perform very differently depending on tuning, cooling, transmission, and chassis design. DACs work the same way.

Marantz is a perfect example in the AV world. In their high-end AV processors, each audio channel is handled by dedicated DAC paths, ensuring consistent performance across large multichannel systems. Stereo DACs, headphone DACs, and AV DACs all have different design constraints—and good manufacturers treat them accordingly.

Hegel notes that while the approach may be similar, the opportunity for refinement increases in standalone DACs:

“Designing a stand-alone DAC offers far more opportunities in designing a low noise DAC.” - Ertzeid

That’s why external DACs often outperform the built-in DACs in phones, computers, and TVs—even when the chip itself is technically similar.

Why Everything Sounds Digital Before It Sounds Analog

Every digital audio device contains at least one DAC, and often several:

-

Smartphones: DAC for speakers, DAC for headphones, DAC for Bluetooth

-

Laptops: DAC for headphone out, DAC for internal speakers

-

TVs: DACs for internal speakers, ARC/eARC output, and headphone jacks

-

Soundbars and powered speakers: multiple DACs handling different drivers

-

AV receivers: DACs per channel, often dozens in high-end systems

And here’s the critical point:

The weakest DAC in the chain can bottleneck the entire system.

You can own great speakers, excellent amplification, and high-resolution music—but if the DAC feeding that chain is compromised, everything downstream suffers.

This is why audiophiles gravitate toward external DACs. It’s not about redundancy—it’s about control.

The Case for External DACs

External DACs offer several advantages over integrated solutions:

1. Better Power Supplies

Phones and laptops are noisy environments electrically. External DACs isolate audio circuits from CPUs, GPUs, radios, and displays.

2. Dedicated Clocking

Good DACs use precision clocks designed solely for audio timing, reducing jitter and improving coherence.

3. Superior Output Stages

Analog output design is where much of a DAC’s sonic character is defined—and it’s often the first thing compromised in compact devices.

4. Longevity

A good DAC can outlast multiple source devices. Your laptop may change every three years; your DAC can last a decade.

But longevity comes with challenges—especially as software and hardware ecosystems evolve faster than ever.

When Technology Moves Faster Than Audio

One of the hardest realities for DAC manufacturers today is keeping up with source devices.

Apple, Google, and Samsung release new chipsets and operating systems every year. USB implementations change. Power management changes. Audio stacks evolve.

Even companies known for bulletproof engineering aren’t immune.

Chord Electronics learned this firsthand with the original Mojo 2 when Apple introduced its proprietary silicon. Some users experienced sudden white noise events—an alarming issue that turned out to be a synchronization failure, not a DAC flaw.

Chord’s Mitch Duce explains it clearly:

“The problem was a loss of synchronisation between source and DAC because of an ISO flow error… The source was blasting corrupted packets, stripping digital attenuation information.”

In simple terms, the DAC wasn’t doing anything wrong—it was receiving broken data at full scale.

Chord responded by developing alternative USB firmware that muted playback when corrupted packets were detected. They also advised users to maximize source volume and use the DAC’s own volume control—reducing the risk of catastrophic noise.

Still, the incident highlights a bigger issue:

DACs don’t exist in isolation anymore. They live inside rapidly evolving software ecosystems.

Chord’s recent Mojo 2 Gen 2 appears to have addressed these compatibility issues more robustly, reinforcing a lesson the industry has learned repeatedly: great hardware still depends on good digital handshakes.

Streaming vs Non-Streaming DACs: A Fork in the Road

Hegel has taken an interesting approach to this problem. Rather than packing streaming into every DAC, the company deliberately offers non-streaming reference DACs.

Why?

Longevity.

“For a streaming DAC, as little as 3–4 years in terms of being fully capable of all new features. For non-streaming, a lot longer. Things have stabilized a lot.” -Ertzeid

Streaming standards change quickly. Spotify Connect, Roon Ready, TIDAL Connect, Chromecast—each requires certification, updates, and long-term support.

Separating streaming from conversion allows DACs to remain viable far longer. It also allows users to upgrade sources without replacing the heart of their system.

DACs in Headphones and Two-Channel Audio

The same principles apply in headphones and stereo systems.

High-end headphone DAC/amps often outperform built-in phone or laptop DACs because they control the entire signal path—from digital input to analog output—without compromise.

This is why companies like Chord, Hegel, and others continue to invest heavily in DAC architecture rather than chasing new features for their own sake.

Choosing the Right DAC: Recommended Categories by Use Case

Not all DACs are built for the same job. A great portable DAC isn’t necessarily a great desktop DAC, and a reference DAC has very different priorities than one designed for an AV rack. Understanding these categories—and what they’re optimized for—makes it far easier to invest wisely.

1. Portable DACs

Best for: Phones, laptops, travel, headphones, minimal setups

Portable DACs exist because the DACs built into phones and laptops are almost always compromised—by power constraints, electrical noise, or space limitations. A good portable DAC bypasses the internal audio circuitry entirely, handling conversion and amplification externally.

What matters most here is power efficiency, stability across devices, and noise control. Many portable DACs also include headphone amplification and volume control, making them all-in-one solutions for serious headphone listening on the go.

Key characteristics:

-

USB-powered (often USB-C)

-

Integrated headphone amp

-

Emphasis on clean power and jitter rejection

-

Compatibility across operating systems (Windows, macOS, iOS, Android)

Trade-offs:

-

Limited output power compared to desktop units

-

Must keep pace with rapidly changing USB and OS ecosystems

As the Chord Mojo 2 experience showed, portability also means dealing head-on with evolving host devices. A good portable DAC isn’t just about sound—it’s about resilience in a chaotic digital environment.

2. Desktop DACs

Best for: Two-channel systems, nearfield setups, headphone rigs, offices

Desktop DACs sit at the sweet spot for many listeners. Freed from battery constraints but still compact, they can focus on better power supplies, improved clocks, and more robust analog stages.

This is where differences in DAC implementation become most audible. Two DACs using the same ESS or AKM chip can sound noticeably different based on output stage design, filtering, and power regulation.

Key characteristics:

-

Dedicated power supplies (internal or external)

-

Line-level outputs (RCA, sometimes XLR)

-

Often paired with headphone amplification

-

Longer product life cycles than portable DACs

Why they matter:

Desktop DACs are often the most cost-effective upgrade in a system. Swapping a computer’s internal DAC for a well-designed external unit can dramatically improve clarity, imaging, and tonal balance—without touching speakers or amps.

3. AV DACs (Multichannel / Home Theater)

Best for: Home theaters, immersive audio systems, mixed music + movie use

In AV systems, DACs scale horizontally. Instead of one or two channels, you’re dealing with many DACs working in parallel, often one per channel. Consistency matters more than absolute spec dominance.

Manufacturers like Marantz take this seriously by implementing dedicated DAC paths per channel, ensuring tonal balance and timing remain coherent across large speaker arrays. In this context, DAC design is inseparable from DSP, room correction, and system integration.

Key characteristics:

-

Multiple DAC channels operating simultaneously

-

Tight integration with DSP and bass management

-

Emphasis on synchronization and phase accuracy

-

Support for immersive formats (Dolby Atmos, DTS:X, Auro-3D)

Trade-offs:

-

Less focus on “DAC flavor” and more on system coherence

-

Limited flexibility compared to standalone DACs

For home theater, the DAC isn’t about spotlighting itself—it’s about disappearing completely while handling enormous amounts of data reliably.

4. Reference DACs

Best for: High-end two-channel systems, long-term investments, critical listening

Reference DACs exist for listeners who want the DAC to be a stable anchor in their system for many years. These designs prioritize low noise floors, exceptional clocking, and power supply isolation over feature churn.

This is where companies like Hegel deliberately avoid built-in streaming, recognizing that software ages faster than hardware. By separating conversion from streaming, reference DACs can remain relevant long after platforms and services change.

Key characteristics:

-

Heavy emphasis on power supply design

-

Minimal feature bloat

-

Exceptional analog output stages

-

Designed for longevity, not rapid updates

Why they last:

A well-designed reference DAC can outlive multiple speakers, amplifiers, and source components. As Hegel notes, non-streaming DACs benefit from the fact that core conversion technology has stabilized—even as interfaces continue to evolve.

The Bigger Picture: Matching the DAC to the Job

The most important takeaway isn’t that one category is “better” than another—it’s that DACs should be chosen by role, not hype.

-

A portable DAC that excels with headphones may be out of place in a speaker system

-

A reference DAC may be wasted feeding Bluetooth speakers

-

An AV DAC’s strength is scale and integration, not character

What matters is alignment: the right DAC, in the right place, doing the job it was designed to do.

And once you start listening with that mindset, it becomes clear why DACs—quietly, invisibly—remain one of the most important components in modern audio.

The DAC Is the Quiet Decider

DACs don’t get the attention speakers or headphones do, and they rarely headline marketing campaigns, but they quietly decide how everything digital sounds. Every stream, every file, every movie soundtrack eventually passes through one. Whether it lives inside a phone, an AV processor, a soundbar, or a dedicated box on your rack, the DAC is the final translator between the digital world and your ears.

What makes DACs so challenging—and so important—is that they sit at the intersection of hardware, software, power, and timing. The conversion itself may be handled by a handful of widely available chips, but how those chips are implemented is where companies rise or fall. Power supplies, clocks, noise isolation, output stages, firmware, and USB behavior all matter. That’s why DACs using the same silicon can sound different—and why some age gracefully while others struggle to keep up.

The conversations with Chord and Hegel underline a hard truth: designing a great DAC isn’t a one-time achievement. It’s ongoing work. Source devices change. Operating systems evolve. USB behavior shifts. Streaming platforms introduce new requirements. Sometimes the problem isn’t the DAC at all, but how aggressively a source device handles data. When things go wrong, the DAC is often the one blamed—because it’s the last thing in the chain.

That’s also why external DACs still make sense, even in a world filled with competent internal audio. They give manufacturers more control over noise, power, and signal integrity. They let users choose a sound they like and hold onto it longer than the average phone or laptop lifecycle. And in higher-end systems, they allow digital playback to scale with the same care we’ve always applied to analog components.

There’s no single “best” DAC—only the right DAC for a given role. Portable DACs solve problems internal audio can’t. Desktop DACs offer meaningful upgrades without complexity. AV DACs prioritize consistency and scale. Reference DACs trade feature churn for longevity. Each exists for a reason.

The hardest part, as both companies acknowledged, is keeping pace with change. Technology moves fast, and audio lives downstream from every update. But when a DAC is designed with care—when power, noise, timing, and implementation are treated as fundamentals rather than afterthoughts—it becomes one of the most stable, rewarding investments you can make in an audio system.

DACs may be invisible, but they are never insignificant. If digital audio matters to you at all—and today, it matters to everyone—then the DAC deserves more attention than it usually gets.